The Rise of the Crips: A Look into South Central Los Angeles in the Late 1960s

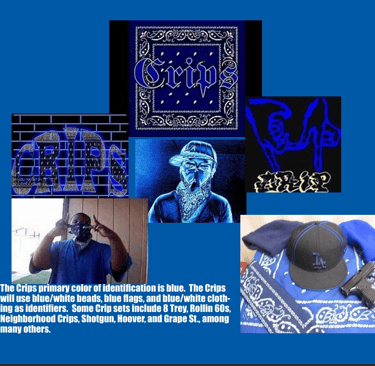

The Crips are one of the most infamous street gangs in American history, originating in South Central Los Angeles in the late 1960s. Initially formed for protection and community solidarity, they quickly evolved into a sprawling network of sets known for their distinctive blue attire, territorial control, and violent rivalries—most notably with the Bloods. The gang’s history is marked by shootings, drive-bys, and high-profile criminal activity, but also by a strict internal code of loyalty and reputation. Today, the Crips exist in a complex mix of street influence, cultural presence, and efforts by former members to steer youth away from the cycle of violence.

GRIM REALITYDISTURBING CASESOUR DREADFUL WORLDABYASSHOPE

9/9/202510 min read

The Blood and the Origin: Of South Central and Crips

The streets of South Central Los Angeles in the late 1960s were a crucible of survival, loyalty, and unrelenting violence. Young men, barely out of their teens, formed groups that would come to define the city’s underworld. Among the earliest were the Crips, a loose alliance of sets initially formed for protection and identity. In 1969, the Businessmen arose, eventually evolving into the East Side Crips before splintering into dozens of sets, each claiming its territory with blood and fire.

The violence was ritualistic, almost ceremonial. Knives, bats, and guns became extensions of the body. Drive-bys were commonplace; vendettas were executed with surgical precision. A glance could ignite a storm of gunfire. Sets like the Rollin’ 60s, Eight Trey Gangster Crips, and Bishops carved their names into neighborhoods with bullet holes and blood-stained asphalt. Loyalty was life, and betrayal was punished with death.

Founders like Stanley “Tookie” Williams and Raymond Washington carried influence that extended beyond their immediate sets. Their presence commanded both fear and respect, and their words were law. South Central’s culture was coded in colors, slang, and gestures—a language of survival. Every corner, every block was mapped in memory, every neighbor observed, every rival noted. Those who failed to follow the rules paid the ultimate price.

In the late 1960s, South Central Los Angeles emerged as a complex tapestry of social dynamics, marked by survival instincts and the formation of community loyalties. Against a backdrop rife with systemic inequalities and limited opportunities, young men navigated a landscape characterized by violence and struggle. The streets became a battleground where the quest for identity and protection led to the formation of various groups, shaping both the neighborhood and the city as a whole.

Among the various factions establishing themselves during this turbulent period, the Crips emerged as one of the earliest organized groups. Initially conceived as a loose alliance of young men aiming to provide protection from rival gangs and external threats, the Crips were more than just a gang; they represented a cultural identity shaped by the struggles of their members. The beginning of this organization can be traced back to 1969 when a group, later known as the Businessmen, began to coalesce. As they evolved into the East Side Crips, this alliance set off a chain reaction that would lead to the emergence of numerous subsets, each laying claim to specific territories through the use of violence.

The Rituals of Violence

The violence that defined the gang scene during this era was not only rampant but also ritualistic. It became a currency for respect and survival among the youth. Tools of violence, such as knives, bats, and firearms, were treated as extensions of oneself rather than mere objects. The prevalence of drive-by shootings transformed the streets into a landscape of fear, where a fleeting glance could ignite hostilities, and vendettas were executed with a chilling, almost surgical precision. This regularity of violence created an environment where the unpredictability of life became the norm, and the streets served as a constant reminder of the stakes involved in this brutal subculture.

In summation, the late 1960s in South Central Los Angeles bore witness to the rise of the Crips amidst a crucible of survival, loyalty, and violence. These young men sought to forge identities and carve out spaces for themselves amidst chaos. What began with a desire for protection transformed into a sprawling organization that would evolve over the decades, forever impacting not just their community, but the entire fabric of Los Angeles. Understanding this critical period in history offers essential insights into the socio-cultural factors that contributed to the formation of gangs, highlighting the human experience underlying the headlines often associated with violence and crime.

Notable Crips and Sets: Heroes and Horror

During the late ’70s through the ’90s, certain sets became infamous for their brutality and influence. The Rollin’ 60s, the Eight Trey Gangster Crips, the Bishops, the Neighborhood Crips, and the Hoover Crips each left indelible marks on the city. Leaders and influential members were revered yet feared; Tookie Williams, Raymond Washington, and others cemented the violent mythology of the streets.

The era produced a mix of legendary feats and tragic bloodshed. Stories circulate of drive-bys that left walls drenched in blood, rival members shot in alleys, or executions carried out in front of witnesses to send chilling messages. The psychological toll was immense—families living in constant fear, neighborhoods becoming war zones, youth indoctrinated early into a violent hierarchy.

The 1980s: Crack, Chaos, and Rise of Notoriety

The 1980s escalated into a new kind of warfare. The Crips’ involvement in the cocaine and crack trade made them both wealthy and more deadly. The Bloods emerged as natural rivals, igniting conflicts that would leave the streets soaked in blood. Shootings became routine; innocent lives were often collateral damage. Children played amid bullet-riddled houses, learning early that survival was dictated by speed, caution, and loyalty.

Infamous incidents illustrate the sheer brutality of this era. Drive-bys became signatures of revenge, bodies were dumped in alleys, and rivalries turned even mundane arguments into life-or-death encounters. A single disrespect could spark multi-block shootouts; lives ended over grudges, minor slights, or territorial disputes. The Crips’ culture, once about protection and brotherhood, devolved into cycles of unrelenting violence.

Music reflected this reality. Hip-hop began documenting the streets with an unflinching eye. Albums captured shootings, betrayals, and street life in ways newspapers never could. Yet for every celebrated figure, hundreds died anonymously, their deaths unrecorded except for whispers in corners and the silent mourning of families too terrified to speak.

The 1990s: Fragmentation and Senseless Violence

By the 1990s, the Crips’ influence had spread nationwide, but with fame came internal fragmentation. Sets began clashing among themselves; young members often failed to grasp the codes of the past. Murders occurred over trivialities—graffiti, disrespect, social media slights, or territory disputes that escalated out of control.

The chaos became almost absurd in its senselessness. The once-structured world of loyalty and protection transformed into a landscape where killing became habitual, almost expected. Violence was now normalized, ritualistic only in its repetition. Streets were littered with bodies, and every news cycle seemed to carry the echo of more senseless deaths.

Yet amidst the carnage, some voices persisted. Former Crips, older members, and community leaders began mentoring youth, trying to instill principles that went beyond retaliation. They organized workshops, community meetings, and music initiatives, teaching younger members the history of their sets while offering alternative paths to survival. Programs emphasized education, legal employment, and community engagement, seeking to replace cycles of death with cycles of growth.

Music as Mirror and Medium: Banging on Wax

Hip-hop served both as a chronicle and a cautionary tale. Projects like Banging on Wax captured the reality of Crip and Blood life, translating street violence into lyrics that shocked, fascinated, and educated. Artists chronicled shootings, rivalries, and the brutal code of the streets, often in explicit, gory detail. The music was raw and unfiltered, a mirror for a generation steeped in violence.

Yet the medium also offered hope. Through mentorship programs and music-focused initiatives, some former Crips worked to channel the creative energy of youth into art rather than bullets. Songs told stories of survival, loss, and loyalty, but also of transformation and potential redemption.

Crimes, Murders, and the Bloodied Streets

The streets of South Central Los Angeles from 1969 through the 1990s were soaked in blood, every alley, crack house, and abandoned lot a theater of brutality. The Crips’ rise wasn’t just a story of turf and power—it was a carnival of gore, a relentless choreography of bullets, blades, and bodies. Early sets like the Rollin’ 60s, East Side Crips, Neighborhood Crips, 8 Trey Gangster Crips, and countless smaller factions claimed blocks in bloody battles where a single misstep could end with a spray of bullets tearing through skulls and chests, sending friends and enemies alike sprawling in crimson.

In the 1970s, Los Angeles’ neglected neighborhoods became pressure cookers. Poverty, systemic oppression, and disintegrating social structures made the streets a breeding ground for extreme violence. The roll call of victims reads like a horror script: Stan “Tookie” Williams was linked to a series of murders where victims were riddled with bullets, shot point-blank in alleys or sprawled across cracked concrete, their lifeless eyes staring up at the indifferent sky. Drive-bys, ambushes, and retaliatory hits were standard operating procedure—entire blocks scarred by spray-paint messages, shattered glass, and the smell of spent gunpowder.

Notable murders weren’t abstract statistics—they were spectacles of terror. Nathaniel “Iron Man” Woods, gunned down in a downtown street hit, was found with multiple bullets through his chest and head, his body contorted in agony, lifeblood pooling into the cracked asphalt. In the mid-1980s, a feud between East Side Crips and rivals escalated into a series of night-time ambushes: bodies left in alleys, their throats slit, some doused in gasoline and set aflame to send a horrifying message. Drive-bys didn’t just maim—they tore apart families, sometimes shredding innocent bystanders caught in the crossfire. Limbs, blood-soaked jackets, and the echoes of screams became grotesque markers of control and warning.

As the 1980s rolled on, the violence only intensified. Turf wars were punctuated by ritualistic brutality: heads smashed with bats, victims tortured for information, sometimes executed in public spaces as grim lessons to rivals. The Rollin’ 60s gained notoriety for blasting entire houses during daylight, turning walls into bullet-riddled canvases, leaving behind shattered glass, scorched furniture, and pools of blood. Even minor slights could trigger a chain reaction: a rival seen on the wrong corner, a disrespectful gesture, or a betrayal would end in execution-level punishment—sprays of lead through car windows, knives slashing throats, victims left in vacant lots for hours until the smell of death drew law enforcement attention.

In this grim theater, modern figures like Blueface, NLE Choppa, and formerly affiliated artists like Bobby Shmurda and Snoop Dogg inherited an environment steeped in lethal precedent. But unlike the territorial, purpose-driven slayings of the late 20th century, today’s violence often feels impulsive and senseless. A young Crip might fire into a crowded street over a social media insult, a fleeting rivalry, or a minor robbery—bullets tearing through bodies indiscriminately, leaving shattered families in their wake. The code of honor that once governed retaliation has splintered, replaced by a chaotic hunger for fame, reputation, or viral notoriety.

Yet, amid the gore and chaos, some older members of the Crips and community leaders have emerged as reluctant heroes, trying to stem the tide. Former killers, once architects of terror, are now mediators and mentors, guiding young gang members away from the cycle of revenge and death. “Banging on wax”—turning aggression into musical expression—is one of the few modern outlets for youthful rage, providing a bloodless way to settle disputes or assert dominance. Community programs focus on redirection: workshops, counseling, and hands-on mentorship aim to convince young Crips that the streets don’t have to be soaked in blood for them to prove themselves.

Even with intervention, the streets remain haunted by their past. Bodies from the 70s and 80s litter the memories of those who survived—some shot in drive-bys, others found dismembered in alleyways, their blood and brains splattered across walls. These historical scars serve as grim reminders of what the neighborhood endured: limbs severed, throats carved, heads caved in, victims sometimes burned or left to rot in the sun for hours. The lessons are clear: the violence is absolute, gruesome, and unforgiving.

In spite of the gore, efforts to reverse this cycle continue. Mentorship, community intervention, and musical expression offer pathways away from bullets and knives. The new generation, influenced by older Crips, law-abiding citizens, and community organizers, may yet redirect their rage into art, business, or social change. But the ghosts of South Central’s blood-soaked streets linger—vivid memories of past murders, mutilated bodies, and the carnage of territorial wars that claimed hundreds of lives.

The history of these murders, their gore, and the sensory terror of South Central’s streets is crucial to understanding the weight carried by today’s figures like OG Cartoon and the 53rd Avalon Gangsta Crips. They are the inheritors of a bloody past, attempting to navigate a modern landscape where the lessons of the streets—once marked by brutal discipline and honor—are now being rewritten in efforts to save lives rather than spill them.

Modern Crips: Celebrity Influence and Changing Dynamics

Today, Crips continue to influence culture, though in more complicated ways. Artists like NLE Choppa, Blueface, and formerly Bobby Shmurda, as well as icons like Snoop Dogg, carry gang-affiliated histories into mainstream visibility. Some glamorize the lifestyle; others attempt to redirect influence positively.

Yet the senseless violence persists. Shootings over trivial disputes, retaliatory attacks, and internal feuds claim lives far too frequently. Social media has intensified conflicts, accelerating cycles of retaliation and magnifying disputes that once might have remained local and contained.

Still, modern interventions show promise. Older Crips, former leaders, and community activists mentor younger members, emphasizing historical awareness, education, and constructive outlets. Music, entrepreneurship, and media have become tools to channel energy away from the streets. These efforts aim to break cycles of revenge and replace automatic retaliation with dialogue, mentorship, and opportunity.

53rd Avalon Gangsta Crips and OG Cartoon

Amid the chaos of both past and present, the 53rd Avalon Gangsta Crips (AGC) stand as a lineage of loyalty, discipline, and identity. OG Cartoon, a four-star General of the AGC, embodies the lessons of an era where one’s word was sacred and retreat was unthinkable. The AGC traces its origins from the Businessmen of 1969, through the East Side Crips, to its present iteration. Lives have been lost defending their honor, and Cartoon carries the weight of those sacrifices with a profound sense of responsibility.

Now living in Alabama with his wife, Cartoon has transformed his experience into something constructive. Through his YouTube channel, Cartoon 53, he shares his life, thoughts, and lessons with his Foundation Nation. This platform allows him to mentor younger audiences, imparting street-earned wisdom while advocating alternatives to violence. Cartoon’s work illustrates that influence can extend beyond the barrel of a gun—legacy can be about guidance, history, and community.

The 53rd Avalon remains a testament to continuity amid chaos. While other sets struggle with internal feuds, senseless killings, and social media escalations, leaders like Cartoon demonstrate that historical knowledge, discipline, and mentorship can reshape narratives. Allegiance doesn’t have to end in death; survival, wisdom, and respect offer greater power than bullets and retaliation.

Conclusion: Legacy, Blood, and Hope

From the gory streets of South Central’s past to today’s ongoing struggle for guidance and safety, the Crips’ story is a tapestry of violence, loyalty, and potential. The bloodshed of 1969–1990s serves as a grim reminder of what occurs when survival is dictated by fear and retaliation. Yet the present demonstrates that change is possible.

Through mentorship, community outreach, music, and media, some former and current Crips work tirelessly to redirect younger generations. They stress education, legal opportunities, and cultural awareness as antidotes to senseless death. Figures like OG Cartoon and the 53rd Avalon exemplify the possibility of transformation: living proof that legacy need not be measured in bodies, but in guidance, wisdom, and the preservation of identity without the endless cycle of killing.

The Crips’ history is written in blood, but its future can be written in choice. And for those willing to listen to the lessons of the streets, there is a path away from chaos, toward influence, purpose, and life beyond the shadows of the past.

Sources

History of the Crips – BlackPast.org

https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/crips/

Provides a detailed history of the Crips, including their founding in South Central Los Angeles and evolution over the decades.LAPD Gang Unit Archives – Crips

https://www.lapdonline.org/gang-unit

Offers official documentation and statistics on Crip-related gang activity in Los Angeles."Crips and Bloods: A Guide to an American Subculture" – Herbert C. Covey, 2016

Academic analysis of the Crips’ origins, social structures, and influence in American culture.Los Angeles Times – "Crips and Bloods: A Timeline of Gang Violence"

https://www.latimes.com/projects/la-me-gangs-timeline/

Chronicle of major incidents, rivalries, and key figures in the Crips’ history.Rolling Stone – "Inside the Life of LA's Crips"

https://www.rollingstone.com/culture/culture-news/inside-la-crips-photos-photos-132331/

Feature on contemporary Crip sets, culture, and members, including interviews with former and current affiliates.

Despair

A dark exploration of societal decay and despair.

Void

+1234567890

© 2025. All rights reserved.

Any comments, business inquiries, ideas, or stories, let us know